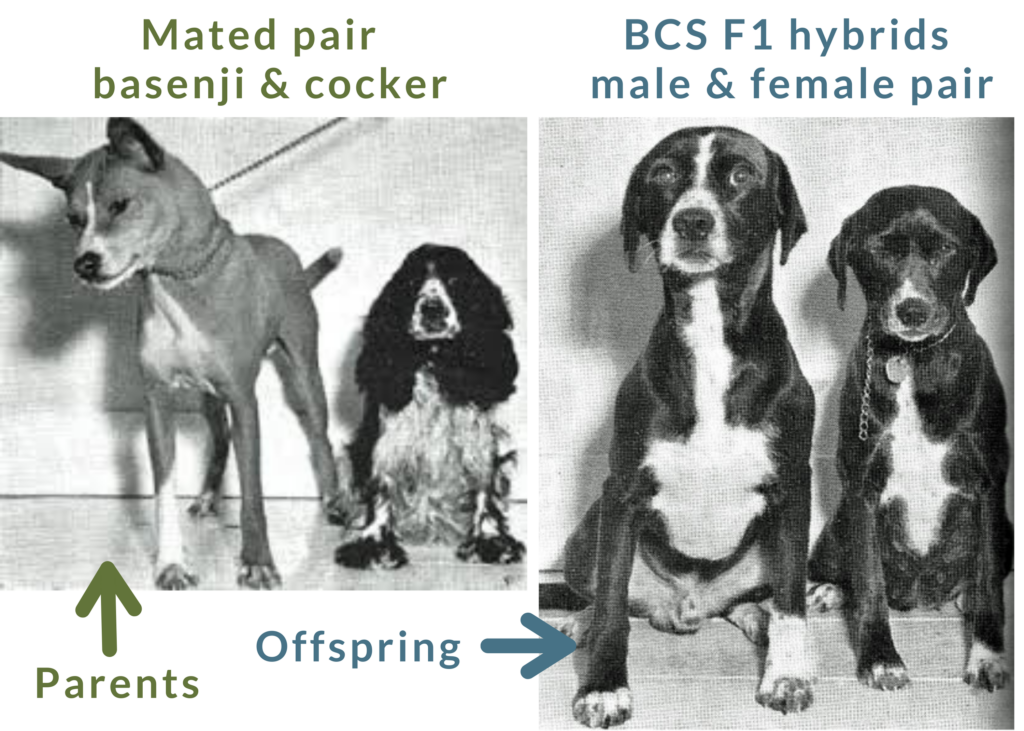

Research has consistently shown that visual breed identification is very often inaccurate1,2,3,5,8, and scientists have known for decades that even first generation crossbreeds usually look dramatically different than either parent6. Moreover, recent research also indicates that even experts have very little agreement when visually determining breed2,4,5.

For additional information, please see: National Canine Research Library Summary & Analysis: Comparison of Adoption Agency Breed Identification and DNA Breed Identification of Dogs

A second study2 by Dr. Voith and colleagues looked at both the validity of visual breed identification and inter-observer reliability, even among experienced canine professionals, using the same dogs as the above-referenced study. Both were very low. Fewer than half of the 923 participants visually identified breeds that corresponded with the DNA analysis for 14 of the 20 dogs.

Separate, additional visual breed identification research was conducted at the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Florida3,4,5, which further confirmed the unreliability of visual breed identification used by dog adoption agencies, animal control, and in regulation.

The first3 was an expanded 2012 survey of over 5,000 dog experts – veterinarians, breeders, trainers, shelter staff, groomers, rescuers, and others – who visually assessed breeds in dogs in a series of photographs. Their assessments were then compared to DNA breed profiles of the dogs. For the purposes of the survey, a response was considered “accurate” if it named any of the breeds DNA analysis had detected in the dog, no matter how many other breeds had been detected, and whether or not the breed guessed was a predominant breed in the dog.4 Since, in almost every dog multiple breeds had been detected, there were lots of opportunities to be correct. However, the respondents were only correct in naming at least one of the breeds detected by DNA analysis on average less than 1/3 of the time. And no profession did significantly better than any other. Every profession’s responses, in total, were correct less than 1/3 of the time.4

For additional information, please see: How long before we discard visual breed identification?

The second study5, which was published in 2015, also explored validity of visual breed identification when compared to DNA, as well as consistency among experts. The researchers specifically focused on visual identification of “pit bull-type dogs,” because they are commonly targeted in breed-specific legislation (BSL). Because the term “pit bull” does not denote a specific breed and there is no agreed-upon definition of “pit bull-type dogs” – not in science, the law, kennel clubs, or animal shelters – the authors defined the term for this study to include Staffordshire bull terriers, American Staffordshire terriers, and American pit bull terriers. The 16 study participants were specifically selected because of their routine visual breed-identification duties in animal shelters, hence the decisions made by this group regularly have real-world consequences. Participants visually identified dogs in their kennels, and then assigned a primary breed and a secondary breed if they chose. If a participant labeled a dog as any of the aforementioned breeds or “pit bull” or “mix” with any of the labels, their breed assignment was considered a DNA match for the study if the test results showed 12.5% or more of American Staffordshire Terrier or Staffordshire Bull Terrier. Thus the criteria for a “match” were extremely broad, including multiple breeds and very low DNA material percentage.

The median agreement between visual identification and DNA analysis for discriminating between “pit bull-type dogs” and “non pit bull-type dogs” as defined by the study ranged from 67-78%. The average sensitivity for visually identifying “pit bull-type dogs” as defined by the study was 50%. Of the 95 dogs who fell into the “not pit bull-type” group by DNA analysis, 38% were nevertheless given the label by at least one breed assessor. That is a significant finding; of the dogs whose DNA did not reveal contributions from Staffordshire bull terrier or American Staffordshire terrier, more than 1 out of 3 were still labeled what the study grouped as “pit bull-type” by at least one staff member. In sum, the overall validity (specificity and sensitivity results) even with such a broad target for identification, did not reach the level of a coin toss.

For additional information, please see: National Canine Research Council Summary & Analysis: Inconsistent identification of pit bull-type dogs by shelter staff

An additional study7 published in 2014 sought to compare U.S. and U.K shelter staff and volunteer’s level of agreement regarding dogs they labeled “pit bulls.” There were 470 participants who indicated that their role involved assigning breed to dogs based on visual identification. Participants completed a breed identification survey online in which they viewed 20 dogs and completed questions such as what breed they would assign to each dog and whether they consider the dog to be a “pit bull.” There was not strong agreement between or within the shelter workers in the two countries in terms of visual breed identification, and like Olson, et al.5, this study also showed that there were discrepancies regarding which breeds are considered to be “pit bulls”. There was not strong agreement between or within the shelter workers in the two countries in terms of visual breed identification, and like Olson, et al.5, this study also showed that there were discrepancies regarding which breeds are considered to be “pit bulls” (a term which has no agreed upon definition – not in science, the law, kennel clubs or animal shelters). Unlike the other studies1,2,3,5, there was no attempt to establish either group’s accuracy (e.g., by comparison with DNA results).

For additional information, please see:

An additional 2018 study8 compared animal shelter staff visual breed identification to DNA results at one U.S. shelter. Staff were provided an AKC breed identification book and instructed to use their existing policy of assigning breed labels based on visual inspection, and were allowed to enter up to two breeds (primary and secondary). In the study, a “match” was determined if a breed indicated by shelter staff was the prevalent breed or if both primary and secondary breeds were correctly identified. Prevalent breed was defined as the greatest number of the same breed signatures identified in the DNA results. A prevalent breed in the study could occur at a level as far back as two great grand-parents. In the study, the primary breed labels assigned by shelter staff matched the prevalent breed from DNA analysis 57% of the time. However, 33% of the time, the label given by staff was not in the dog’s DNA, even at the great grand-parent level. That is, for 1 out of 3 dogs, the label given by staff was completely incorrect.

The researchers also analyzed breed labels vs. DNA results for a group of dogs they called “pit bull-types” – a term which has no agreed upon definition – not in science, the law, any kennel clubs, nor animal shelters. Staff were not allowed to label dogs as “pit bulls.” They were obligated to choose a specific breed, with the option to indicate 2 breeds. A dog labeled as one of the four breeds selected in this study as “pit bull-type” (e.g., American Staffordshire Terrier, American Bulldog, Bull Terrier, and Staffordshire Bull Terrier) was considered a match to the “pit bull-type” group if the DNA analysis revealed only one of these breeds to be present at the great-grandparent level (12.5%). The study reported that the larger the percentage of these breed signatures in a dog’s DNA, the more likely it was that one of the breeds would be visually identified by staff. However, this grouping, which, it is important to emphasize, is not a breed grouping recognized by either major breed registry organization, resulted in a much larger target for an “accurate” visual breed identification than for any other dogs. Interestingly, if the staff making the identifications designated an actual breed group (e.g., “Terrier”) this was not considered a legitimate identification for the study and was thrown out. Without creating analogous groups of nearly equally common breeds grouped with morphologically similar breeds, it cannot be assumed that their results would be any different.

For additional information, please see: National Canine Research Council Summary & Analysis: A canine identity crisis: Genetic breed heritage testing of shelter dogs

It has been customary in our society to look at a dog and guess its breed or breed composition. Many scenarios result in a dog’s presumed breed being recorded, including arrival at a shelter, veterinary visits, licensing, housing and insurance applications, doctor visits following dog bites, and the subsequent media reporting of said incidents. Eventually these unconfirmed identifications make their way into databases that are then used in retrospective research studies to make claims about canine behavior. Several studies have sought to relate breed and behavior, dog bites and dog bite-related fatalities. These studies influence public opinion and policy regarding particular breeds. Inaccurate data regarding breed are being propagated, studied, and used to drive policy.

For additional information, please see: National Canine Research Council Summary & Analysis: Rethinking dog breed identification in veterinary practice.

We take very seriously the reliability of the studies on which we report and understand that there are those who are skeptical of breed identification obtained through DNA analysis. Indeed, it is important to note that DNA identification may not be 100% accurate when analyzing mixed-breed dogs. At the time Dr. Voith conducted the first of these studies1, the accuracy of the Mars Wisdom PanelTM used in the studies was reported to be 84%, for identification of breed in F1 crosses (offspring of 2 different registered purebreds). Mars Wisdom PanelTM does not currently report accuracy as a percentage, however their test, which is specifically intended for mixed-breed dogs, uses around 1,800 markers per dog to identify breed and features 350+ breeds.10 Additional companies perform canine DNA tests, but have not, as of July 2019, been used in published visual breed identification studies. (Embark, for example, uses over 200,000 markers per dog to identify breed and features 250+ breeds.)11 It is important to note that when interpreting DNA test results, breeds that show up in larger percentages are more accurate than breeds that show up at very small percentages. For example, a breed that is reported in a DNA test at a level of 5% is less likely to be accurate, whereas a breed result that shows up at the level of 25% is likely to be accurate.

The results of the above-mentioned studies allow us to say with confidence that the accuracy for DNA analysis is much higher than that achieved by looking at the dog for at least 2 reasons:

Understanding how a dog’s appearance is determined by its DNA can also help explain why a DNA test is better than visual breed identification. Visual breed identification is based upon the observation of a handful of variable breed-associated physical traits, such as coat color, body size, skull shape, and whether the ears are erect or floppy. However, these physical traits are found in many different breeds, and a large number of morphological traits are controlled by a small number of genes within the roughly 20,000 genes that make up a dog.12 Sometimes, a breed may exhibit a certain physical trait because all the members in the breed have exactly the same version of the gene that encodes the trait.

If this trait is recessive (for example like the trait associated with long fur), only dogs with two of the same version of the gene will exhibit long fur. If one of these dogs is the ancestor of a mixed- breed dog, the mixed-breed dog may contain both the DNA for the recessive version of the trait (long fur) and the dominant version of the trait (short fur). However, the long-haired recessive appearance will not be observed because the dominant short-haired DNA would determine the visual appearance of coat length (making it short). Subsequently, the visual identification of breed would inaccurately exclude long-haired breeds based upon the visual observation of short hair. The DNA results might report both long-haired and short-haired breeds in the dog’s ancestry even though the dog only has short-hair. Coat length is not the only trait that can be “hidden” from visual observation due to dominant and recessive patterns of genetic inheritance in dogs.

Although the DNA test may not assess every gene or even each physical attribute of a dog, the regions of the genome that it uses to assess breed take into account much more information than visual observation. The DNA test is better than visual breed identification because it takes into account the pattern of genetic variation at many different regions across the dog genome to generate a “genetic snapshot” of a mixed-breed dog’s ancestry. The resulting genetic evidence for which breeds make up a mixed-breed dog may or may not agree with visual observations, but do provide insights into the story told by a potentially chaotic mix of breed ancestries in a dog’s DNA.

While breed identification by DNA analysis is more accurate than visual breed identification, it is important to remember that neither predicts behavior of any particular dog. Each dog is an individual, and its physical and behavioral traits will be the result of multiple factors.