To best understand this article in the context of the visual breed identification literature, please see National Canine Research Council’s complete analysis here.

Article Citation:

Voith, V. L., Trevejo, R., Dowling-Guyer, S., Chadik, C., Marder, A., Johnson, V., & Irizarry, K. (2013). Comparison of visual and DNA breed identification of dogs and inter-observer reliability. American Journal of Sociological Research, 3(2) 17-29. doi: 10.5923/j.sociology.20130302.02.

National Canine Research Council Summary and Analysis:

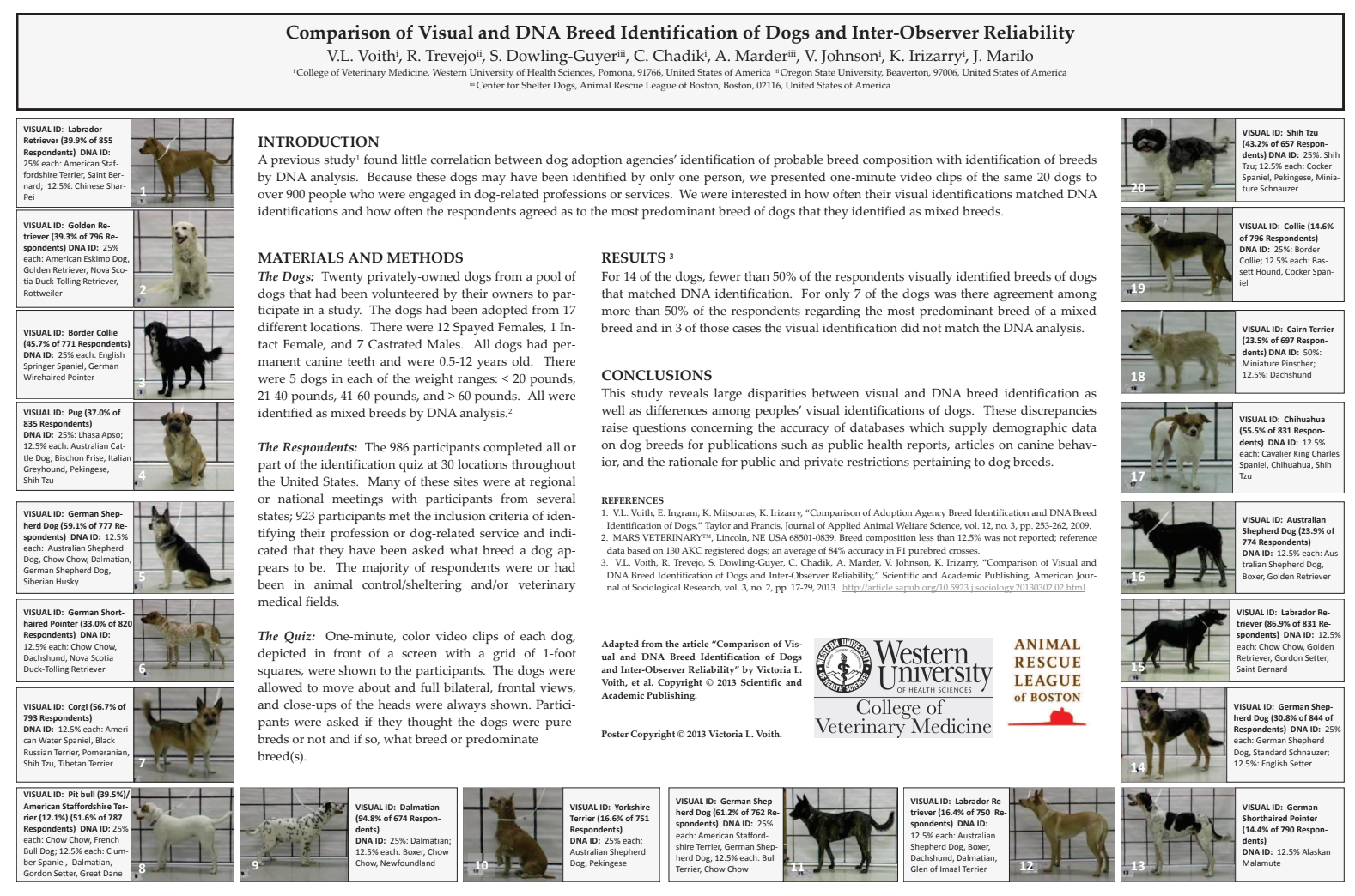

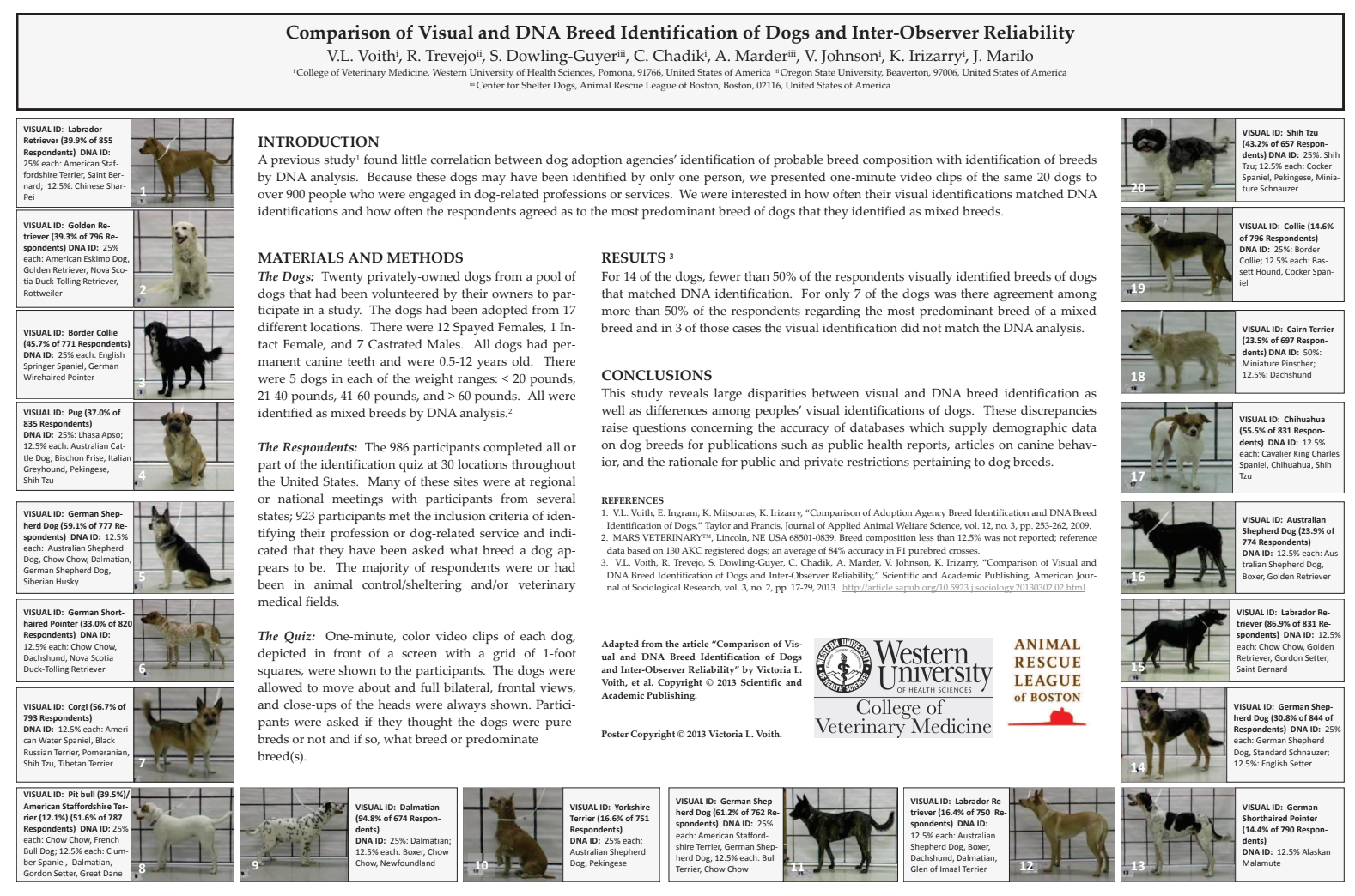

This study examined both inter-rater reliability between experienced canine professionals and validity of visual breed identifications compared to DNA profiles—both were very low. We include this study in our research library because the sample is large, aspects of reliability and validity are both addressed, and the sample is comprised of individuals who regularly label dogs’ breeds by visual identification as part of their occupation. For these reasons, this paper is critical and has important real-world applications.

A large sample of dog professionals (n=923) participated, including individuals from a variety of canine-related backgrounds (e.g., animal control, veterinarians, shelter agencies, dog clubs professions which often provide breed identification and documentation). The twenty dogs from

Voith et al. (2009) were used as the subjects of this study, along with their original DNA results, which determined all breed contributions that comprised at least 12.5% of a dog’s genetic makeup. Participants watched 1-minute color videos of each dog and were told each dog’s sex, weight, and age. Practically speaking this means that all aspects of the dog commonly used to identify breed (ears, tail, build, size, activity level and way of moving) were visible so that the participants would have access to similar identifying features as those in the earlier study (the adoption agency workers who originally breed labeled the dogs for adopters). In fact, the length of time spent viewing the dog (one minute) is not dissimilar to the amount that a shelter worker or veterinarian might use when determining breed.

After each video, participants completed a questionnaire in which they indicated which breed or breeds they believed each dog to be. Specifically, they answered whether or not they believed each dog was purebred, and if so, what they believed the breed is. If the respondent indicated that the dog was not purebred, they were asked to identify the most predominant and second most predominant breeds. If they were unsure of the second breed they could respond, “mix.”

Fewer than half of the participants were able to correctly visually identify any breed in the dogs’ DNA analysis for 14 of the 20 dogs. Moreover, for 3 of the dogs whose predominant breed was agreed on by more than 50% of participants, this visual identification did not match any (major or minor) DNA breed identification. The experts were unable to agree with each other or with the DNA identification. For only 7 dogs (35%) could even half the observers agree on a predominant breed. Thus, in this sample of canine professionals, both inter-rater reliability and validity of visual breed identification were low.

The implications of these findings are incredibly important. Researchers and public policy makers should very carefully examine studies that link breed and behavior; if breed was reported without DNA confirmation or pedigree, the data cannot be considered reliable. Considering the potential severe implications for both the owners and dogs of specific breeds and/or types from Breed-Specific Legislation (e.g., bans, euthanasia, containment, and increased fees), agencies should exercise great caution when labeling a dog of unknown ancestry. If the lineage is unknown and DNA analysis unavailable, a “best guess” based on visual physical characteristics should not be made; it is reckless to do so given these data that demonstrate its unreliability. Moreover, researchers cannot responsibly conduct experiments nor cite studies that rely on visual identification for determining breed. Unless DNA analysis is conducted, or the dog’s parentage is documented by pedigree, specific breeds or breed groups should not be indicated.

Link to Full Text of the Original Article:

Additional references:

Voith, V. L., Ingram, E., Mitsouras, K., & Irizarry, K. (2009). Comparison of Adoption Agency Breed Identification and DNA Breed Identification of Dogs. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 12(3), 253-262. doi:10.1080/10888700902956151

Page last updated June 11, 2019